Nuclear fusion has long held the promise of cheap, plentiful and, above all, clean energy with zero carbon emissions and minimal radiation issues that undermine public confidence in nuclear fission. The UK has been at the forefront of fusion research, hosting the Joint European Torus (JET) at the UK Atomic Energy Authority’s (UKAEA) site at the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, the world-leading fusion tokamak centre. In the recent budget the UK Government allocated an additional £20 million to the UKAEA. This follows a £50 million upgrade of the Mega Amp Spherical Tokamak at Culham, underlining the government’s commitment to the field.

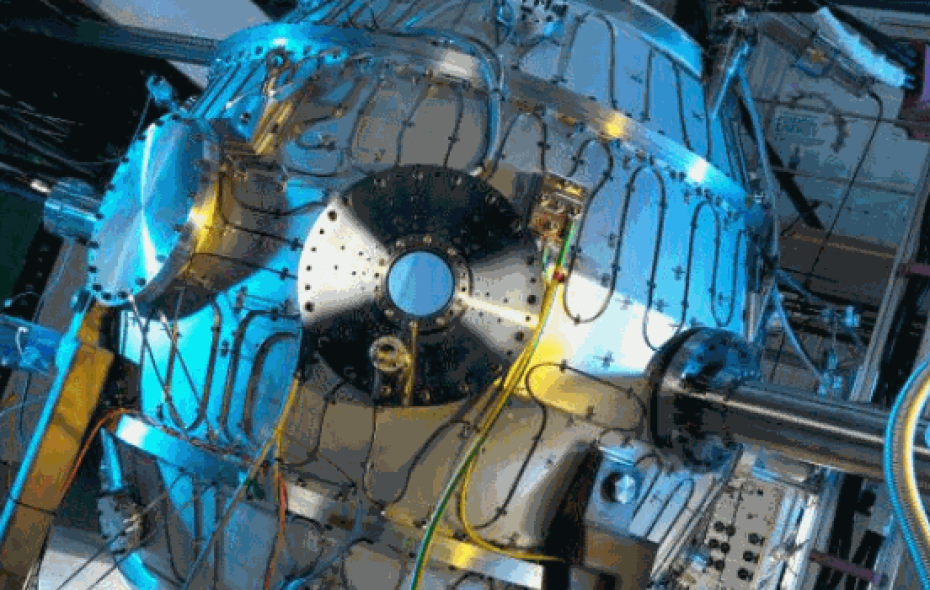

Until a few years ago fusion research was too difficult and expensive to contemplate outside multinational collaborations such as JET and its successor, ITER, now under construction in France. Recently, a handful of private companies have emerged to challenge the conventional view that fusion is still several decades away from realisation. One such company, Tokamak Energy, is developing a design that combines the superior efficiency of a small spherical tokamak (JET and ITER are much larger, doughnut-shaped devices) with magnets made from novel materials. These magnets carry extremely high currents but use a fraction of the space of traditional magnet materials. They have the potential to transform the small tokamak design from a research tool capable of only low magnetic fields into a viable fusion device.

When UKI2S was approached in 2010 to provide the first funding for Tokamak Energy as it spun out from Culham, we were not thinking of solving the planet’s energy issues with fusion. The company’s initial targets were potential applications in medical isotope production, hydrogen generation and nuclear waste disposal. UKI2S invested just £25,000 to fund exploration of these and other applications. This gave the small team a platform to develop ideas, attract further funding, in turn leading to a research prototype and kick-starting work on promising enabling technologies. Within two years Tokamak was well-formed, attracting funding from larger investors. The company has since raised approximately £40m and made significant advancements. Earlier this year Tokamak announced it had achieved a plasma temperature of 15 million degrees Kelvin, as hot as the centre of the Sun. Their device is currently in the middle of an upgrade to allow it to target 100 million degrees Kelvin in 2020.

Kick-starting a company based on emerging science and technology only partially proven is the sort of risk very few investors will undertake, and seeing it make such great strides is highly rewarding. Other fusion start-ups are also making impressive progress and building a sense that fusion could be getting closer. But for all the excitement generated by some of these young companies, there is a great deal of enabling work still required in multiple less glamorous fields ranging from magnet design and robotic handling through to neutron-resistant materials and diagnostic and control systems. No single company can do it all and collaboration is inevitably required to reach the goal of fusion, which is where the public sector may come back to centre stage.

The facilities at Culham, the programmes in essential fields such as robotics and materials handling, and the accumulated knowledge of its scientists are all hugely valuable assets that the UK can deploy in support of the goal of fusion. Tokamak Energy and other fusion start-ups have made very impressive strides and shown how much can be achieved even with limited budgets. But the future – and the achievement of a key goal for mankind - seems very likely to lie in a collaboration between public and private sectors, harnessing the agility of private ventures to the deep knowledge and infrastructure of public centres of research excellence such as Culham.